The first page of Lexicon of the Everyday might well begin with Liu Yi’s childhood.

Born with a congenital leg disability, he was taught by his parents to live with and through painting. Unable to freely go outdoors, his parents would invite neighborhood children to come inside and play with him. In their games of make-believe, Liu Yi was often chosen as “father” or “king” because of his eloquence. He won the affection of his playmates through words and laughter, and they were willing to listen to him and follow his lead.

To Liu Yi, this was itself the love and wisdom of his parents: teaching him, within the limits of his body, a way to connect with others his own age. These childhood experiences became the foundation of his later artistic practice: first carving a path for himself, then offering his self to the world—producing something intriguing, and sharing it with others.

In 2015, Liu Yi began his “mobile phone drawings.” The very first one was for his students: he moved a class from the classroom to the park, turning it into a picnic, and created a poster for it on his phone. Watching his students sprawled across the lawn, he found the scene so delightful that he drew another. From then on, he developed the habit of sketching at any moment, anywhere—on the subway, on the toilet, in the bathtub, at the hospital—never stopping. These works encompass landscapes, still-life sketches, moments with family, reimaginings of dreams, images of body and scars, embodiments of emotion, and compositions where reality and imagination intertwine. In these images, he wrestles with mountain spirits, confronts a giant version of himself, sees mythical birds in flight, and captures a flower-stone in the corner or a passing cloud on the horizon. Much like Carl Jung’s Red Book, these are private diaries in a spiritual dimension—dialogues with all beings and non-beings: with Gilgamesh, with hermits of the desert, with beetles, ravens, and with Philemon. Liu traverses the blurred spaces of dream and imagination, omnipresent.

Rewind to 2013, when Liu Yi was deeply captivated by Japanese ukiyo-e in the British Museum. The small-scale prints resembled fragments torn from a diary, depicting street scenes of Edo-period Japan, landscapes, folklore, and social life. The vibrant lives of all social classes leapt vividly from these little prints. The emergence of ukiyo-e marked the democratization of Japanese art, shifting from aristocratic circles into the lives of ordinary people. Its vitality lay in its portrayal of common life and personal subjectivity. This vitality not only transformed Western art history but continues to inspire the present, studied and reinterpreted by generations. For Liu Yi, this renewed his reflections on the scale and medium of painting, prompting him to experiment with small works. In 2014, the year his son was born, he kept a pocket notebook with him throughout his wife’s pregnancy and their child’s birth, recording intimate domestic scenes during the postpartum month. These daily sketches planted the seed for what later grew into his mobile phone drawings.

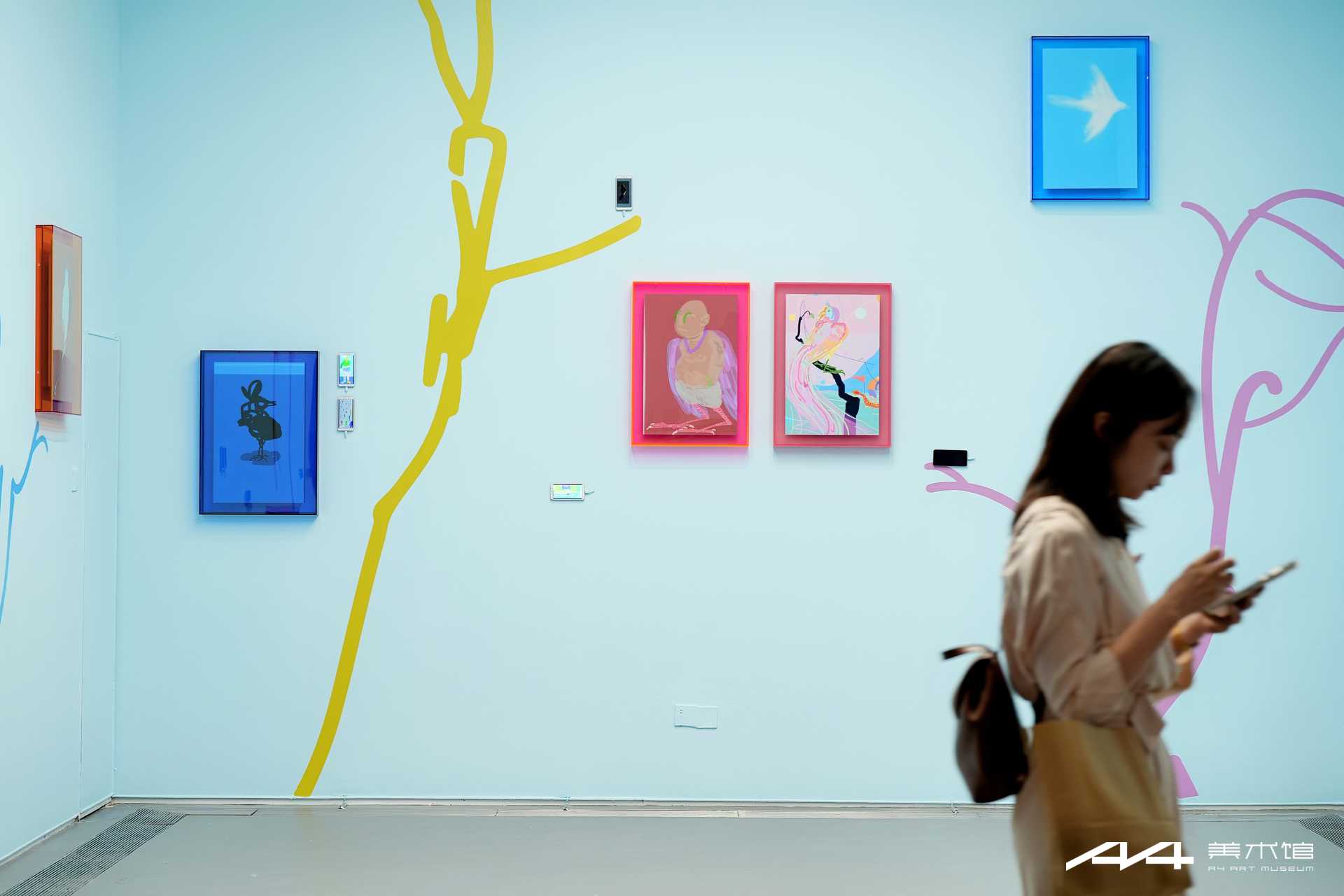

The trace of a finger sliding across the screen becomes image—each carrying its own thought, rhetoric, and syntax. When the phone and the finger become tools, the image is no longer merely a medium of representation but the immediate generation of body and spirit. It embraces the present moment, continues the spirit of ukiyo-e, and flourishes in the soil of contemporary media. If the spread of ukiyo-e relied on woodblock printing and urban circulation, then Liu Yi’s mobile phone drawings rely on the internet and social media. Uploaded daily, they are stumbled upon by unseen viewers—scrolled past, liked, commented on, shared, even downloaded and saved. Within them we glimpse shared histories and experiences, ancestral life and primal imagery reawakened in us. This invisible diffusion has become Liu Yi’s new path of dialogue with the world. Over the decade, the works have also moved beyond the digital sphere into public space—transformed into public sculptures or extended into community-based projects such as Birdsong Radio. The sliding of his finger thus becomes a strategy for bringing people together. Out of the disorder of the everyday, Liu Yi creates a personal order and logic through continual practice. Yet this order is never fixed—just as a lexicon defines words in the present but is always updated in the future. The everyday is constantly rewritten, supplemented, and redefined, unfolding as an open state.

Over ten years, more than five thousand mobile phone drawings have accumulated into a vivid, playful, and life-affirming Lexicon of the Everyday. It turns fragments of daily life into entries, gateways into collective experience, illuminating what is most easily overlooked or dismissed as meaningless, thereby enabling spiritual freedom. Through the symbolization of the everyday, the individual connects with deeper layers of the collective unconscious.

Jung described this psychic process as individuation: gradually integrating and harmonizing the conscious and unconscious, bringing self into dialogue with contradictions and shadows, so that one may grow beyond mere social roles into a complete and unique Self. Liu Yi’s art enacts precisely this. It reveals archetypal images emerging from the ordinary, and allows others, through viewing and participating, to become essential to the work’s wholeness.

Thus, “mobile phone drawing” is no longer a matter of technological convenience, but a path in the making. It is a lifelong, unfinished process: the endless adding of new images, the unseen viewers, the transformations into public art—all constantly expanding its scope. Ultimately, Liu Yi compiles it into a Lexicon of the Everyday: a book of answers, a road toward wholeness, helping us to perceive the infinite and the complete within the ordinary.

“The love of the 336 gods is sheer beauty, but we are mortals. Precisely because we are mortals, I have resolved to become a complete and true mortal.”*

Liu Yi’s art and life are the very reflection of this resolve.

* Carl Gustav Jung, The Red Book. Beijing: China Machine Press, 2016.

Text: Wenzhe Wang